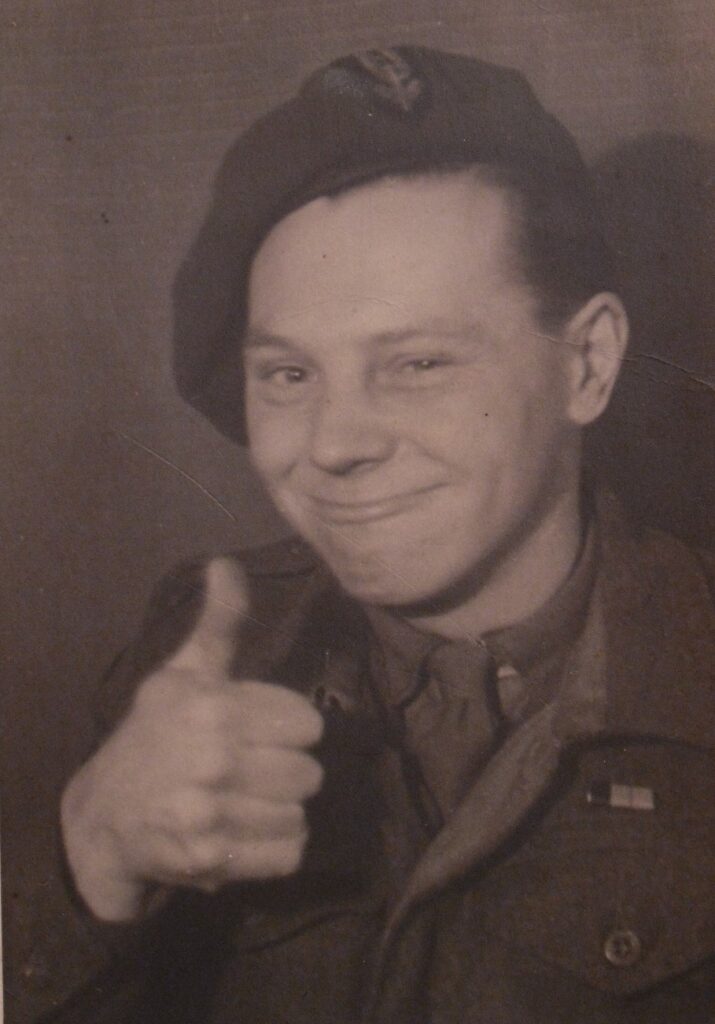

Douglas Cronk

This is a bit of a detour and wanders away from the Favell family history, but does have a tenuous connection. It is a story too important to miss. Douglas is actually the the Great Grandfather of two of my Grandsons. He was the Grandfather of my son-in-law, so is related to my Grandsons, if not me. One of them is named after him.

Doug Cronk was born in September 1919, just two months before the Armistice that ended the Great War. In 1914 his father had received a gunshot wound while serving in France and spent the rest of the war in the UK as a Sergeant in the Bedfordshire Regiment. He had recently been discharged from the army and the family lived in Westcliffe on Sea in Essex.

As a teenager young Doug worked as an ice cream salesman and as war in Europe loomed for a second time, he Joined the Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire in April 1939 at the age of just 19. At the outbreak of war Doug found himself in France and experienced the evacuation from Dunkirk. He later volunteered to become part of the clandestine Auxiliary forces who would ‘stay behind’ and carry out a guerrilla war behind the German lines in the event of an invasion. This is probably how he came to the attention of the SAS and following intensive training in Scotland his records suggest that he was in mainland Europe ahead of D Day.

Doug seemed to relish his training and brawling on a night out in Glasgow was just seen as a part of it. Interviewed by Gavin Mortimer for his book about the SAS, ‘Stirlings Men’, Doug recalled “there was nothing like being put on a “fizzer” (a charge) by the Military Police after a night out in Glasgow for improving your standing within the Regiment. ‘One night we gave some MP’s a bit of lip and they took us to the guardroom and said we would be hearing from them later’ says Cronk. ‘But Paddy just tore up the charges’ (Paddy Mayne).

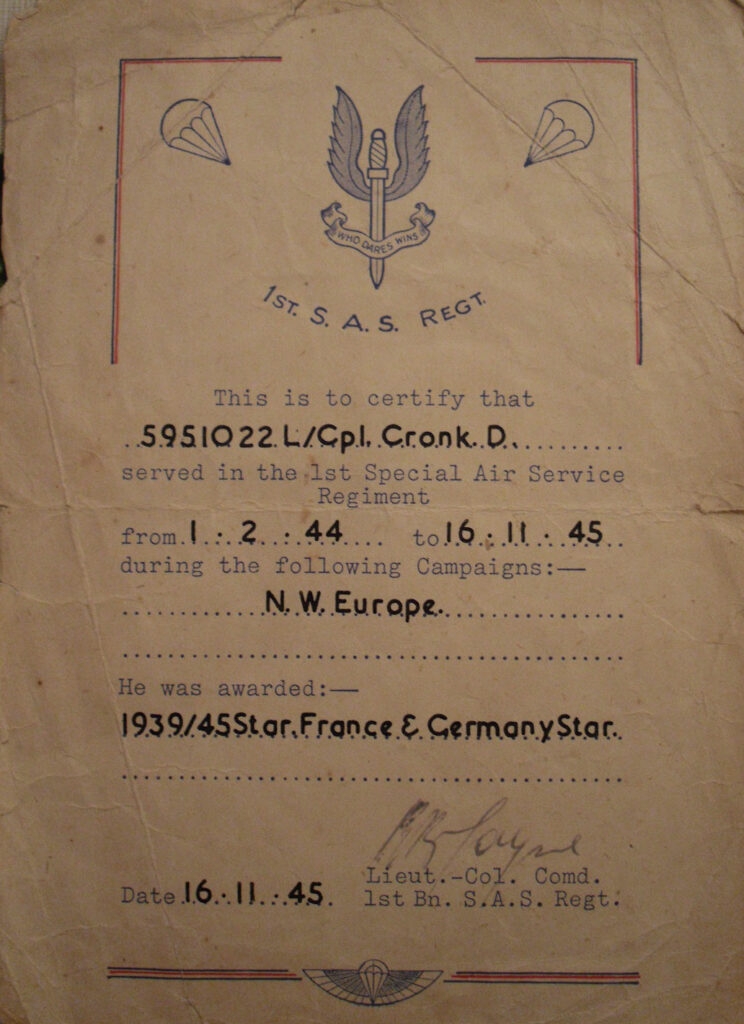

By April 1944, at the age of 24, he was a Lance Corporal in the 1st Regiment SAS. According to another book by Gavin Mortimer, “The SAS in Occupied France,” Doug was a part of Operation Kipling, working behind enemy lines to carry out reconnaissance, attack supply lines and generally cause mayhem to demoralise the retreating Germans.

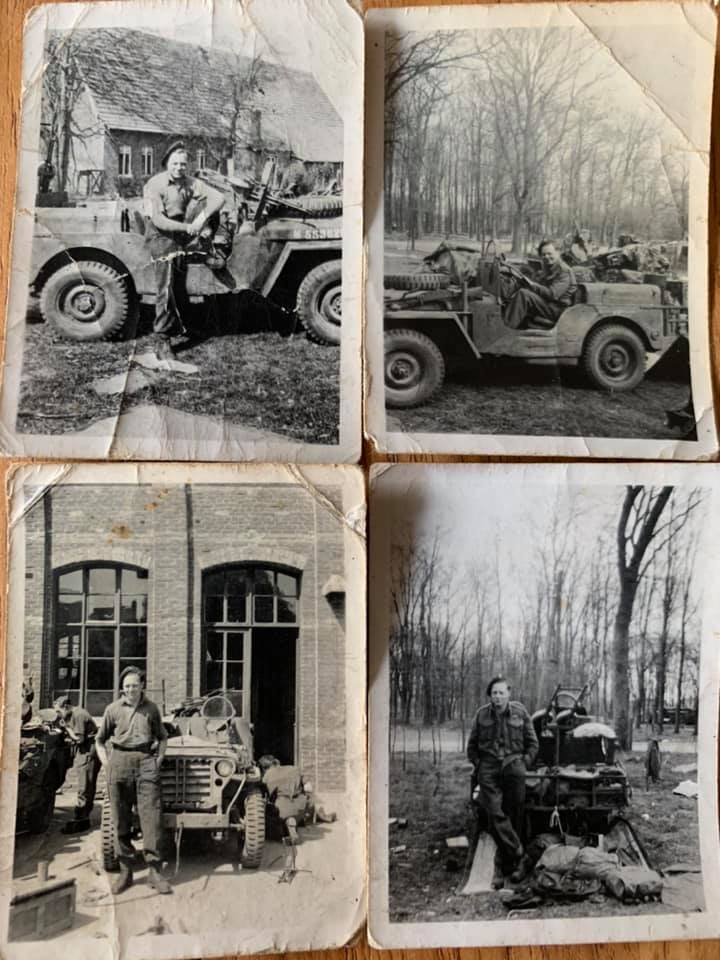

Of particular interest here, is that later, moving through the lowlands and then into Germany, Doug probably broke the rules in so far as he carried a camera with him. This has provided us with some authentic snaps of him, his comrades and their jeeps on active service with the SAS.

Doug later took part in the liberation of Norway where the SAS assisted in rounding up and disarming some 300,000 occupying troops.

The fighting that Doug described in interviews with Gavin Mortimer, in a very matter of fact way, was brutal. But after the war Doug put the memories out of his mind, settled in Dorset with his young family and became a bus driver. He never attended SAS reunions and said “it’s over with now, forget about it. I’ve never had any dreams about the war; I’ve never really given it any second thoughts.’

Quoting from Stirling’s Men by Gavin Mortimer where he describes the ambush of a German convoy near the village of Nannay: –

The men from the leading vehicles spilled out into the woods surrounding the road while the rest of the column hurriedly reversed. There then followed what Davis described in his report as a ‘lively SA (small arms) and grenade battle’. Doug Cronk spotted one German through the trees just as he threw a grenade. “It caught me flush on the chin” says Cronk, “but it didn’t go off because the silly bugger had forgotten to take the pin out. I’ll never forget the look on his face as he realised his mistake”. Cronk shot him dead.

In “The SAS in Occupied France” Douglas says: –

We knew that the German forces were around us and we were told by Paddy Mayne what we had to do if we caught them, because they’d just as soon kill you as look at you. That meant they didn’t live. But you couldn’t take prisoners. They were walking around with white flags, calling you ‘Kamerad’ desperate to give themselves up…. But I looked at it that you got to take an order. They were under similar orders.

Well, we were on this road, more like a track, walking along the edge and these Germans came along riding bikes, fucking horrible things they were, different to anything we had. We saw them coming and we banged them off, about six or so. A couple were still alive so we finished them off. We couldn’t just leave them there, we had to cover our tracks, so we dragged them and their bikes off the track and dug a shallow grave for them in the woods. Funny thing was, we made a small cross out of twigs and put it on top. I don’t know why we did that. A matter of respect I suppose. But could you have respect there, in a war? I suppose you can.

We’d captured a German boy, about 17 or 18. We questioned him and then Sergeant McDiarmid said “Right, clear off”. And this German walked away and as he did, Mc Diarmid shot him. I thought “I don’t know about that, that’s not right”. Why did we let him do it? I don’t know. We were shocked.

When I got demobbed I didn’t want to know anything about it (the SAS). My view was “it’s over with now, forget about it”.

He moved to Dorset with his young family and became a bus driver.

‘I’ve never had any dreams about the war; I’ve never really given it any second thoughts.’